1. Over the course of ten years, you tracked both your communication and movements. How did that affect your behaviour or, in other words, did you actually change the way you walk through the city?

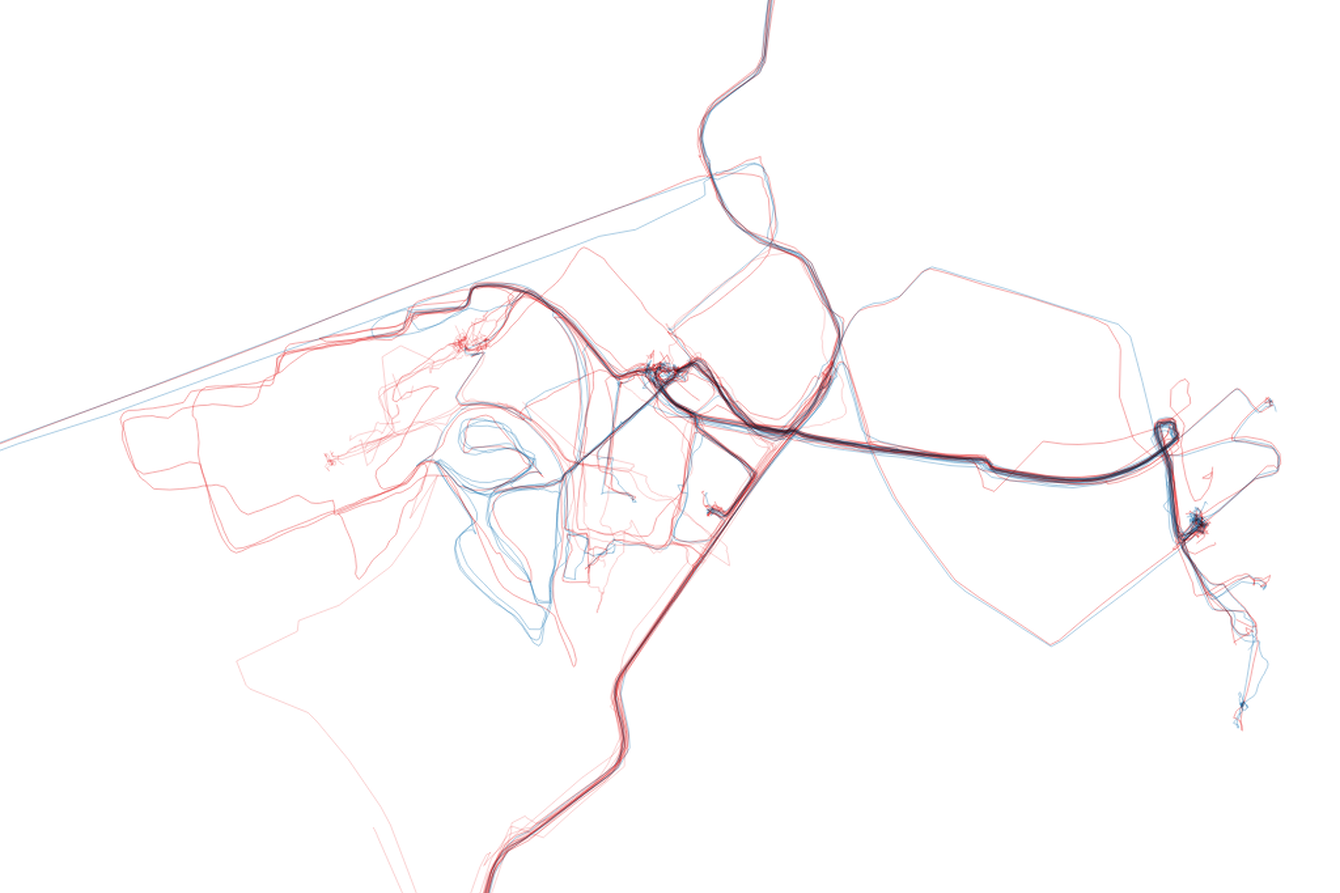

In the early days in 2003 Dan used to walk on the curb in order to get better GPS reception and I often had to stop him walking into lampposts (actually he made another piece about his accidents in cities called ›Unfallen‹). I think that doing this practice for over a decade there is a certain about of automation, for instance we often turn our GPSs on and a few moments later wonder if we have done it and check again – it is as if our bodies know what to do and our minds are slower to catch up or sometimes doubt the body memory. I think we also are potentially excited when we are on 'new turf', i.e., walking in an area, city or place for the first time knowing it initially exists as a single line or otherwise unexplored territory. However it is not our intention to fill in blank parts of our maps but rather to have a recording of our lives lived, like a rubbing, facsimile of the places we go to.

2. You are using the data as a material, transforming it into objects and thereby something that we consider to be "immaterial” is becoming a physical object / a material artwork. What are your thoughts on this and can you elaborate on the process?

Digital processes and data produce vast quantities of information that needs to be stored, processed and archived. The devices and storage solutions are changing, within our times as a duo we have moved from storing on CDs, to DVDs to hard drives with numerous back ups and we have still managed, through burglaries and human error, to loose stuff. Actually what we have realised is that paper, and objects can potentially last longer than digital material so to transform that data into a material object is a way of securing that information for the future. Sometimes we make large maps as inkjet prints or with a plotter, or we re-draw our traces, we engrave into other materials (plexi-glass or granite) and most recently we have made data rugs from the data that we call ›Knotted Time‹. As well as having exhibitions we are also interested as performers in telling stories about the objects we create – this gives another dimension to the abstracted material, how we will secure those stories that we often tell live remains to be seen – perhaps through word of mouth or living on in the memories of audience members. We should probably write a song they seem to have longevity too.

3. Many people argue that the digital revolution has connected the world – people are connected over great distances and friendships can span all over the globe. In general, how do you feel that togetherness has changed due to the massive technological changes we have experienced over the last decades? And how did these affect your personal sense of working collectively as artists?

As artists who have increasingly become politicised about data, who owns it and how is it used, we have opted not to be part of social media and use open source software and linux. This choice has its drawbacks – we have to work harder to stay connected – write personal emails, physically give people cards/maps and talk face to face – our presence is not disseminated remotely and as widely as others – we need to remind people we have a website. I guess we might then lack the extended presence and feeling of togetherness that others might have, but I have heard many times that mediated presence does not really replace physical interaction and the online performed self is constructed with varying degrees of success and failure. Increasingly as partners and parents we realise there is no substitute to spending time together, in fact one of the tricky questions is to ask oneself how much time do I need with that person or activity in order to feel connected? We are constantly fighting for that time amongst all the other obligations and considerations we have in order to survive.